The time by car between any two of Tennessee’s big cities—Memphis to Nashville, Nashville to Knoxville, Knoxville to Chattanooga—is under five hours. In our search for great virtual teams, we make the drive east from Nashville in the center of the state on 1-40 on an early summer’s night. The sun setting behind us colors the sky ahead, painting the peaks that become the Appalachians the shades of their names. Here, where Tennessee, Virginia, and North Carolina converge, the Blue Ridge meets the Smoky Mountains.

Smoky blue turns to black by the time we top the last hills to our destination. Suddenly a surrealistic “whiteprint” of light flashes below us, shimmering strands of luminescence that sparkle for acres, pipes pushing up to 90-degree turns then angling down into elaborate twists of conduits. A spaceport? A city of the future? Tucked away in the small town of Kingsport is one of the world’s largest chemical manufacturers—and an acknowledged world-class management system.

It is in this valley conveniently situated on both a navigable river and railroad that, at the urging of a local entrepreneur, George Eastman decides to invest in a defunct chemical plant in 1920. He needs a reliable chemical supplier for his developing photography business some 700 miles to the north, Eastman Kodak Company in Rochester, New York.

Three quarters of a century later, Eastman Chemical Company, which spins off from Kodak in 1994, is a $4.6 billion global operation with approximately 15,000 employees manufacturing more than 400 products. It’s an e-commerce leader in the chemical industry. Although you cannot go into the corner store and buy anything with the Eastman label, you would have a hard time not buying something with an Eastman product in it. Need a toothbrush? An Eastman chemical is an ingredient in the plastic handle. Soft drink, beer and liquor bottles, pain killers, peanut butter, tires, carpet, cosmetics, stonewashed jeans, computer chips, garden hoses, medical devices, laundry detergent, latex paint, tennis balls, and, of course, photographic film all contain Eastman chemicals.

Today Kodak is still one of Eastman Chemical Company’s largest customers, but it is only one of 7,000 who buy its products around the world. Nestled in the northeast corner of Tennessee, Kingsport is the chemical company’s world headquarters. Manufacturing operations stretch across five American states, as well as Argentina, Belgium, Canada, China, the Czech Republic, Denmark, England, germany, hong Kong, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, The Netherlands, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Taiwan, and Wales.

In 1993, Eastman becomes the first chemical company to receive the U.S. government’s highest kudo for quality, the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award. We first report on Eastman in The Age of the Network.1 There we tell the story of a traditional firm that reinvents itself as a networked organization while still retaining important elements of hierarchy and bureaucracy.

It takes a quality crisis of business threatening proportions—and nearly two decades of work—to move the company to the network structure it now has. The company begins its renaissance in the late 1970s when it loses market share of a major product due to poor quality. With a focus on traditional quality approaches and a lot of common sense and creativity, Eastman goes about redesigning how it does its work from the shop floor to the very top of the company. Today, everyone works in teams and usually in multiple teams.

Ask people at Eastman why they win the Baldrige Award and they will point to their quality philosophy that rests on team alignment. “It’s a consensus style of management,” says Earnest Deavenport, who becomes Eastman’s CEO in 1989, “that is much more based on team than individual decisions. There is more empowerment of teams than you find in a conventional organization. Many fewer decisions get bumped up to me to make individually.”

Eastman is a complex mix of permanent, temporary, face-to-face, ad hoc, geographically distributed, culturally diverse, vertical, and horizontal teams. Some have traditional team leaders. Some rotate leadership. Some are quite formally chartered. Others less so. There are multiple executive teams and hundreds of shop floor teams.

Almost all Eastman teams cut across space, time, and/or organization boundaries.

Eastman has all types of virtual teams. It has shift teams that are responsible for keeping operations going around the clock. Short-term project teams are invariably cross-functional. While sometimes co-located, more often these teams follow the typical pattern of coming together and then going apart. They meet as necessary to plan and align their work then carry it out individually or in smaller groups.

Longer-lasting process teams are distributed and cross-organizational, like customer and supplier teams. Although most virtual teams need some face-to-face time together to function effectively, especially at the beginning, they can become “more virtual” over time. Eastman has a supplier team, for example, that had many face-to-face encounters when it began but increasingly fewer as time passed. Once the group established trust and set up its processes of interaction, it continued to make quality improvements without meeting. The virtual team functioned asynchronously in different places and organizations.

Because Eastman is a manufacturing operation, good teamwork on the shop floor is synonymous with good quality in its products. One of its earliest “improvements” comes as a simple recognition in the late 1970s: the four shifts per day are simply one ongoing team spread out over 24 hours.

“At that time, we have a ‘tag and you’re it’ shift change mentality, four different people around the clock running four different shift teams,” says Will Hutsell, Eastman’s senior associate in Corporate Quality. Very little information passed between shifts. When one shift leaves, the next would come in and readjust all the control room dials, as if the people before them have no idea what they are doing. Operators have to ask permission to make any changes and, of course, they punch time clocks.

During the initial implementation of continuous improvement efforts, Eastman takes groups of the shift foremen off the job for quality management training. Instead of working their normal shifts, they come together as a group for training and planning improvement projects. These foremen (who are now called team managers) then go back to their work areas and hold team meetings with their operators to develop plans for implementing the projects.

Change comes quickly. The operators have the skills and information they need to do their work without asking anyone’s permission. In time, they stop punching time clocks. Operations improve enormously and control rooms are clean. Eastman is on its way to a Baldrige.

Today, Eastman’s training process is a sophisticated operation that reaches across the company. For example, to be trained as coaches, people leave their jobs for 12 weeks of intensive education in modern management thinking, skill building, and practice. Initially, they set up training programs and had people attend individually, but they find that approach not to be very effective. So groups of managers start attending together, creating sufficient critical mass of shared experience in the organization to sustain the learning when people return to their jobs.

At the same time that Eastman reinvents work on the shop floor, it also makes many other significant changes that raise the trust level in the company:

It equalizes benefits across the organization. Everyone has the same vacations for years served and everyone has access to the same healthcare plan.

It eliminates the traditional performance appraisal system that distributes people’s performance across a bell curve and replaces it with an employee development system.

After experimenting with team rewards, it stops them because it proves impossible to draw indisputable lines around “the team.” Individual teams depend on the overall inter-team environment; they cannot succeed without it. Eastman now has a company-wide bonus program tied to the company’s financial performance.

All Eastman teams have a vision and a mission and most have charters and sponsors. In many cases, teams accept a written charter with a signing ceremony that commissions the teams.

“Because there are many teams at Eastman, it is essential that we always define the purpose of each team,” Hutsell says. Without clear purpose and an established process for defining it, confusion not quality would rule at Eastman.

“Typically a broad charter is put in place and the team is empowered to see if it makes sense,” he says. “The team can modify its own makeup.” Using Eastman’s Quality Management Process, teams pay attention to such questions as: Do we have the right purpose? And do we have the right membership? This helps keep teams on track.

“You must look at the purpose,” Hutsell cautions. “Only when you have that right can you get from here to there.” Eastman’s early attempt to use one of the most fundamental quality tools, Statistical Process Control, a quantitative method for improving quality, fails when the company tries to implement it without fully making clear its connection to purpose.

The best predictors of virtual team success are the clarity of its purpose and the group’s participation in achieving it.

Eastman teams thrive in a culture infused with purpose. Purpose starts at, but is not dictated by, the top. The Senior Management Team is the keeper of the Strategic Intent, the document that contains the company’s vision (“To be the world’s preferred chemical company”) and its mission (“To create superior value for customers, employees, investors, suppliers, and publics.”) The Senior Management Team is also custodian of the document known as “The Eastman Way” that sets out its values and principles. The document makes explicit the culture required to support teams working across organizational boundaries. It also serves as the touchstone for innumerable changes that make a difference in the day-to-day working life of Eastman employee-owners.

While written down and published, the Strategic Intent is also a dynamic document. It serves as the framework for overall long-term company strategy and shorter-term initiatives known as MIOs, Major Improvement Opportunities. Everyone in the company is involved in the planning process. Organizations bring the knowledge of their part of the business—specifically including customer needs, competitive comparisons, company and supplier capabilities, and risk assessments—together with the Strategic Intent to develop Strategic Alternatives. These are then formally submitted to the Eastman Executive Team that forms the overall strategy and makes selections among alternatives.

With the strategies set, the organizations develop goals, their own MIOs, and their criteria for success, known as the key results areas. With concrete measures in hand, the virtual teams develop plans using Eastman’s Quality Management Process in which everyone in the company is trained. Eastman’s version of the familiar “plan-do-check-act” continuous improvement cycle adds a step at the beginning. Before “plan,” there is an “assess organization” step where the team focuses on clarifying its purpose in interaction with customers and in alignment with the company’s strategy.

Early in its team journey, Eastman makes a mistake that many companies do: They convene teams and focus on the mechanics of the meetings such as following agendas and drafting plans without giving the teams a clear purpose. That turned around when the teams took on specific projects with clearly defined expectations. Eastman values time spent gathering information, developing and choosing among alternatives, creating implementation plans, monitoring and documenting progress, celebrating results, and even formally disbanding. The process itself generates continuously increasing value.

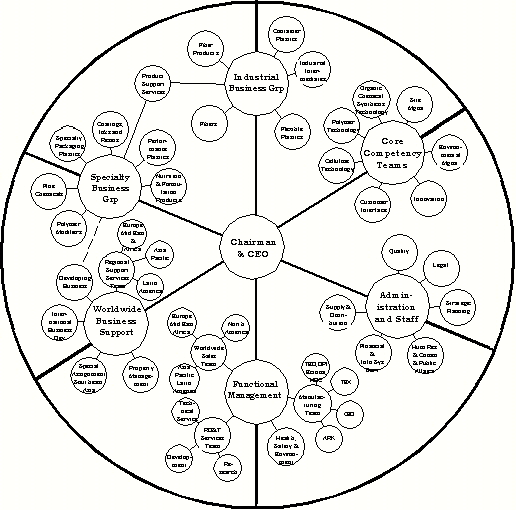

For people interested in organizations, Eastman is famous for its unique organization chart, its “pizza with pepperoni.” Hierarchy, bureaucracy, networks, and teams all have their place in this organization-in-the-round (Figure 7.1). The company expects people to communicate horizontally not vertically. There is no going up a chain of command, across to another function, and then coming back down another chain of command to get something done.

Deavenport creates the now-famous circular chart in 1991, he says, because he wants “to signal the organization that this was a different structure, a networked structure, a team effort, not business as usual. We’re all in this together.” While the chart preserves the logic of hierarchical levels, “the artist in you has to come out to see the pizza chart as different from a hierarchical one,” Deavenport comments.

Eastman uses a truly cross-sectional approach in showing how its hierarchy, bureaucracy, and network fit together in a 21st-century organization. The central and foreground position of the chairman and CEO, Earnie Deavenport, symbolizes hierarchy. Structurally, his position anchors the hub-and-spoke locations of the six major corporate components. Bureaucracy is well represented both in the general use of specialization and purpose—every sub-group has a unique name and mission—and in specific components devoted to maintaining traditional bureaucratic functions.

What makes the Eastman chart uniquely indicative of an Information Age networked organization is its periphery. This heavy outer circle attaches directly to all the major components and represents the direct connections among the divisions. Deavenport talks about the “white space,” where collaboration takes place and work gets done. In the circle, he repeats, “no one is on top.”

“Work gets done across and within and between functions. Major processes in the organization have to go horizontal. A lot of important work doesn’t get done in the vertical sense,” Robert Joines, a former manufacturing vice president explains.

Still, there’s a place for hierarchy, he says. “Sometimes Earnie [Deavenport] has to make decisions no one else can. You can’t stamp out hierarchy and run an organization. You have to have vertical alignment. To be successful, you have to learn to do both of these together. Our interlocking teams are a hierarchy in a sense, and then we turn hierarchy on its side.”

Nothing is more important to the virtual team than its clear purpose. Discovering it is the team’s first priority. Once found, purpose locks into place the source of virtual legitimacy and power.

Hierarchical groups can fall back on force as their source of authority. Bureaucracy can turn to rules and regulations. Virtual teams and networks require something more to mold and hold them. When new organizations emerge, so do new premises of authority and power. To see how authority works in the Network Age, we need to start at the beginning.

Charisma and tradition rule nomadic cultures.

Nomadic authorities have the ability to influence others but not force them to do anything. Leaders, including those surviving today, claim authority by demonstrating competency, inspiring passion, and recalling the voices of the ancestors.

Eventually nomads rooted permanently, tending farms and building cities. Hierarchy arose.

Hierarchies use force to defend resources, maintain social stability, and control technology.

In business, the people who sit at the top of the hierarchy—the owners—have the power to hire and fire, to give out rewards, and to inflict punishment. They may promote and demote employees, grant and refuse raises, acknowledge people or place them on probation. The extraordinary power of owners is nowhere more evident than in their exclusive right to start, buy, sell or merge a business as a whole or in parts. When Shell Oil Company partnered with Texaco to create three new companies to handle their downstream retail business, 7000 Shell employees and a comparable number from Texaco moved companies. Today Shell, tomorrow Equilon, and there you are having to bond with a new culture that’s never existed before.

When agriculture gives way to industry, brute force yields to the rule of law.

Bureaucracies use rules, regulations, policies, and procedures to gain authority. In this rule by law, bureaucrats get their power from their place in the administrative structure. Traditionally, each rank has its own legal perks.

Purpose is central to all small groups and teams. It takes on a new aura in virtual teams. Because traditional authority is minimized, they need some other guiding force.

Virtual teams develop an inner authority based on everyone’s commitment to shared purpose.

Strategic alliance teams comprise people from different companies. They lack common reporting structures or policies since people in them come from different hierarchies. In cross-functional teams, the best-known virtual team, no common authority figure may tie everyone together until they reach the CEO.

In the beginning, someone has an idea. It spills out in a meeting or on a phone call, and maybe gets firmed up on an e-mail. Conversations begin, others are inspired and recruited. Presto: A virtual team has the essential glue. Inside or outside formal channels, within a company or between firms, ad hoc teams self-legitimatize through common purpose.

A new species of authority often appears long before it becomes dominant. Law emerged thousands of years ago in the hands of Hammurabi and Solon2, much earlier than the rise of constitutional governments like the United States that subordinated military force to democratic rule. From laws, rules, and regulations, Industrial bureaucracies constructed new dominant modes of authority.

Just as each age strengthens a previously limited source of authority, so does it bring a new basis for power, the other half of the governance equation.

In virtual teams, power comes from information, expertise, and knowledge, the new reservoir of wealth.

Peter Drucker regards knowledge as so critical now that he uses the plural—we need multiple “knowledges” to survive.3 His advice: “One cannot manage change. One can only be ahead of it.” Knowledge workers are capital assets not costs, he says.4 How did people become so valuable? Today’s tasks require brain not brawn. Specific expertise is in great demand. Experts have always had power but not the kind they do today.

People come together with hope that by combining efforts they can achieve something great. To get to their desired results, they divide up the work. Most tasks require people with specific skills, capabilities, and experiences. Such folks have power to the degree that their participation is critical (Figure 7.2).

Virtual teams have an especially tough job. They need to cope with all the traditional power people and they must harness the information and knowledge-power people.

Though the jury is still out on how companies will reward and punish virtual teams, hierarchy clearly has far less influence in the new world.

The importance of position varies enormously in virtual teams. Some individuals come to the virtual team as anointed leaders. In others, everyone temporarily (and sometimes uneasily) sheds their ranks and takes on new identities. Formal positions still exist, but they do not necessarily determine who takes precedence in virtual teams.

Because of their ability to reach anywhere for members, virtual teams can easily include people with a wide diversity of knowledge and skills. By deliberately seeking difference, the team reaps the creative benefits of a broader range of viewpoints and expertise. Diversity becomes the differentiator.

Everyone on a virtual team needs to be expert in something the group requires. The more important the work, the more highly valued the required skills. Like architects, consultants (relatively pure instances of people with expertise power) build teams to work on a specific project then build another team to satisfy the needs of the next project. Each team’s members differ depending on its requirements.

Purpose sustains and initiates process. It is the source of life for all teams, the inner fire that gives them their vitality. Here, virtual teams face two particular challenges that differ from those of co-located teams:

First, it costs more to mature purpose in virtual teams, both in terms of the length of time it takes to mature and in the literal expense of bringing together distantly situated people. On the other hand, a purpose set well can be a source of economic benefit: Coordination costs fall when committed people align around the same goals.

Second, purpose is more important when people are all spread out than it is when a boss is watching over everyone’s shoulders.

For resource-lean and information-rich virtual teams, good organization design mirroring the work makes for better results. As the team carries out its original intent, the organization re-forms to address new goals and the next pieces of the work. People reconfigure continuously. Today, it’s Don, Kate, and Celia working on Pfizer. Tomorrow it’s Kate, Jeff1, Jen, and Carrie working on the offering. The day after that it’s Annie, Jeff2, and Jessica working on recruitment. Our organization, like most others, constantly re-forms, organically adapting to the dynamic unfolding of the work.

Virtual team success or failure begins with the relationships among people and goals. Nearly a half-century of empirical research demonstrates the power of cooperation in teams.

Social psychologist Morton Deutsch is the first to use goal interdependency to predict how well people work together. He asks whether people see their goals as cooperative, independent, or competitive relative to one another. The more interdependent the goals, the more successful the team.

Cooperation occurs when people have compatible goals. When you succeed, I succeed. Confidence and trust are expected behaviors. Cooperation generates positive feelings of family and community as people share and integrate information.

Independence results when goals are not related. Your success or failure has no bearing on mine. I do not expect any support or hindrance from you. Aspirations are personal and relationships between us are less personal. We all do our own thing and have no need to share.

Competition follows from incompatible goals and the belief that if you win, I lose. Your success diminishes mine. I not only expect no help but I anticipate hostility and prepare accordingly. To prevail in competition rather than be integrated in cooperation, people hoard information and use it as power.

Dean Tjosvold, Professor of Business Administration at Simon Fraser University in Canada, is at the forefront of team researchers bringing a wealth of learning from hundreds of studies into real-world practice.5 He reports that myriad studies document this simple fact:

Cooperative goals motivate team members.

When goals are compatible, people strive to succeed and work becomes meaningful. Cooperation brings added benefits of helping others, feeling good, and storing goodwill for the future. It spurs information sharing and greatly expands insights available for planning, problem solving, and execution. Confident of success, people believe that others want them to do well. They have more fun, which translates into more positive feelings about work. Most important to problem-solving and related tasks, cooperation results in higher productivity than competitive or independent work, a wide range of studies agree.

Researchers’ conclusions about competition within a “team” don’t surprise anyone. It does not motivate people to share information, plan together, or find the best path for producing results. Competitors do not expect others to help or encourage them. What competition can do is galvanize the team as a whole against another team. It motivates people who believe they have superior ability and are likely to win, but it demoralizes people who have (or believe they have) lesser abilities and experiences. Competition also can motivate when tasks are simple and information needs are low, providing most of the people believe they have a chance of winning. However, since sharing information is the lifeblood of a virtual team, competition within hinders or scuttles success.

Whether intentional or not, tasks and rewards always generate cooperation, independence, or competition.

Joint rewards for group tasks promote cooperation. When cooperating, people assume that everything is fair and expect corresponding rewards. They pool their talents, offering and using individual skills and competencies as needed by the tasks. People appreciate creative conflict as a tool for finding the best answer.

Unrelated tasks, separately rewarded, encourage independence. Quotas or sales targets measure individual success, separate explicit external criteria. People use their abilities to further their own goals. They avoid conflict, regarding it as a distraction from separate pursuits.

Co-dependent tasks—separate pieces of work that require a winner and a loser—create the environment for competition. Such systems need rules to regulate the games. People use their abilities against one another. They avoid conflict entirely or deliberately escalate it to gain personal advantage.

Most work situations are complex and involve a mixture of motives. Tasks that are set up interdependently require cooperation. At the same time, people compete for attention, praise, promotions, and raises while also taking pride in their individual accomplishments.

Typically, people encourage cooperation within a team to better compete with outside groups. One familiar archetype of this behavior is the great sports team—for example, the Boston Celtics basketball team in the 1970s whose internal teamwork is legendary, propelling them to one championship after another. Such us-against-them behavior is considerably more tricky in work organizations. Many a successful team that bonds into a tight family also excludes and competes with outsiders. Unfortunately, outsiders to the team may still be insiders in the organization. A company with many teams ultimately wants all of them to cooperate for the good of the enterprise.

However cooperation fares inside the corporation, can we still safely assume competition takes over at the enterprise boundary? For hundreds of years, the simple rule has been to cooperate internally and compete externally. This maxim is under fire. Countless alliances explode across corporate boundaries. The Internet ties companies closer to vendors and customers. Competitors and non-competitors cooperate all the time wedding unlikely partners, like the Muppets and Ford Motor Company.

Purpose sparks life in virtual teams. This discovery brings people together, builds trust, and gets things going. To survive, teams must turn their purpose into action, using it to design their work and organization. Some teams receive a fully formed charter; others go off with a vague sense of desired direction. Some team members think that setting purpose is important while others do not. Most team experience lies between these extremes as people struggle to understand and express their purpose.

Purpose is the campfire around which virtual team members gather.

We use the word “purpose” to stand for a broad range of terms—from abstract vision to increasingly concrete mission, goals, tasks, and results. While teams may vary from organization to organization, how they relate to one another is important. Purpose is a little system of ideas; it expresses itself differently across the organization while synthesizing into common harmonies.

Vision is the inspiration for purpose-driven organizations, the source that generates the flow of work. When articulated best, vision includes a compelling picture of the achievable, highly desirable future. Vision is also the realm of values and philosophy, the intangible but crucial culture of ethics, norms, and the intrinsic value of people that bring life to virtual teams. It does not have to be long.

Eastman’s vision is short, simple: “To Be the World’s Preferred Chemical Company.” The word “preferred” carries both the customer focus and the implied strategy of superior quality. Other organizations create lengthy vision statements. The Massachusetts Teachers Association, with 75,000 members—one of the largest unions in the Commonwealth—has a vision statement that covers a page. Regardless of length, it’s the painting of the future.

Mission is the simple statement of what the group does, the strategy that expresses its identity. Though usually more specific than the vision, it remains abstract. A flower importer answered marketing expert Ted Levitt’s famous recurring question, “What business are you in?” with one word: Love. Not transportation or agriculture. In a world of fast-changing markets, this question usually goes to the heart of organizational transformation and the teams it spawns.

Goals state what we're going to do, translating intangible lofty visions into palpable, practical results. They reformulate the mission—the singular overall goal—into a few manageable sub-missions. Goals provide motivation, the starting point for work process, the original formula for dividing work into its components. Goals allow you see desired outcomes in the future. Embedded in goals is the strategy for turning vision and mission into positive results. The smarter the goals, the better the strategy. Discovering this virtually takes time.

Tasks are the doing, “how” the work gets accomplished, the actions that arise as goals go into motion. Invariably expressed in action verbs—develop, design, identify, create, tasks specify the actions members take. Tasks are the team’s signature, its mark on its world. Purpose becomes quite practical when people do their tasks. But because they are in constant motion, tasks can be somewhat slippery to the materialist grasp.

Results thud into place as the concrete outcomes of purpose, the done. Reports, presentations, events, products, decisions—outcomes that everyone understands—clearly express purpose. The team creates something through its work. For a task action to be complete, there is always a result—however grand or poor—within a given period of time. It is in the nature of the task-oriented team to produce and judge itself by its end products.

Since we are genetically programmed to see results as “things,” it is often hard for virtual teams to make their results concrete and tangible to people. Making results explicit is one of the primary benefits of creating online places to do collaborative work.

To put purpose into motion, plan.

The better the planning, the more effective the process. Better processes mean less time, less cost, and more customer satisfaction. Many groan at the thought of planning, harking back to numerous memories of shelved plans, quixotic decisions by higher authorities, or perhaps detail to a level of mind-numbing minutiae. As bad as planning can be, there is simply no other way. Virtual teams must build purpose refinement into its work process. This means planning.

We all know how to plan naturally—in a general sort of way. We do it all the time. It follows a basic pattern that we use repeatedly every day—the path. Each time we envision a result that we act upon, we conjure up a little bit of planning, whether to go to the kitchen to get a cup of coffee, to the store to get a magazine, or to the website to get some information. We have an image of what we want in our minds (a goal) and we rehearse the steps (planning the tasks) that will take us to get what we want (the result). Then we set off.

Goal Tasks Results

These interrelated terms reflect the universal pattern of work: A motivating source, a target at the end, and steps that connect the source and the target over time.

Short paths or long journeys, the logic is the same. Most of the journey lies in the middle, between goals and results, in the province of tasks, the doing. While tasks are points along the path, the pieces of work that fit together over time, process is the sequence of actions. Each task is itself a little bundle of activity. Results do not just appear by magic at the end; they grow over time in the course of doing work, performing tasks.

There is a natural flow to purpose. Like mountain streams seeking springs, purpose runs from the heights of abstract vision to concrete valleys of results. Putting purpose into action over time produces a dynamic picture of work (Figure 7.3).

Vision flows into mission, which becomes the highest-level goal. To accomplish the overall purpose, segment mission into sub-goals, the first steps toward the division of labor. Tasks are the specific steps taken to achieve results. Some steps are serial, each dependent on the one before. Other tasks are independent and parallel, coming together at the end or interdependently across tracks of parallel activity. Most virtual-team work is a mix of these modes.

Virtual teams truly are microcosms of the organizations that spawn them. This becomes increasingly evident the higher the group is in the organization. At the top, the senior team most literally and directly expresses that truth. There all the work components come together, and the organizations of all the major players cross boundaries.

Put into the language of purpose, the organization’s structure provides a way to break down its work. Look to the interplay between goals and tasks to see this little recognized but profound fact of business life: Goals at one level generate tasks at the next level, where the assignment is in turn taken on as a goal. Cross-hatching work across levels is a familiar, natural and practical way to organize teamwork. Although not a conventional framework, the goal-driven view of work offers teams a perspective on how their work interrelates (Figure 7.4), essential for extensive enterprise-wide virtual teamwork.

Pfizer Pharmaceuticals Group cascades its goals, says Joe Bonito, who heads the company’s organizational effectiveness and consulting efforts. The CEO, Hank McKinnell’s, goals “go down to line executives, who translate them to marketing and research. It’s an excellent system.”

Where does the vision come from? The board of directors, representing the owners (i.e., shareholders), sits at the top of the organization together with the highest ranks of senior management. In most business organizations, senior management generates the vision and provides direction, whether bold or timid, vivid or obscure, conscious or unconscious. They establish a hierarchy of goals, based on what the owners want: Profit, growth, social, and other returns of import to them.

To reach these positive corporate results, the company creates value through its work. Most permanent organizations segment the work literally, setting up divisions and departments (both derive from the same root word meaning divide). Each has its own mission—for example, marketing, research and development, engineering, production, sales, and distribution departments (functions) or divisions based on factors such as products, geographies, or industries. To make its contribution to the joint work effort, a large organizational component like marketing may further subdivide its piece. Internally, it creates its own departments and groups, each of which has separate charters (written or “just understood”) based on the work assigned from above. This sequence replicates down and throughout the organization, with each group doing its own work and expected outcomes.

So it goes down the line, with a person from this level serving on an implied cross-functional team while also serving as head of the team at the next level down.

While the importance of discovering purpose does not by itself distinguish virtual teams from traditional ones, the depth and clarity of its expression does. The purpose problem is two-fold for virtual teams:

Crossing boundaries of space, time, and organization only further complicates already complex communication. An inherently messy process of creating a coherent, productive, and lasting purpose in the early stages of a team’s life is even less tidy for a virtual team. It needs dense and frequent communication.

Once developed, the team must make the purpose and plan explicit in symbols, words, diagrams, tools, handbooks and persisting virtual places. The plan must stay updated, flexible, and adaptable in order to serve as a coordination hub for distributed work.

The problem with a complex purpose lies in people’s need to grasp it simply. Establishing purpose requires first a conceptual solution, then a display solution, and finally a navigation solution.

“Periodically, we go back to our original purpose, our shared mental model. Building such a model has been extremely helpful in communicating across geographies and cultures. Some teams produce explicit pictures of what their mental models have become in terms of numbers and graphics. It gives us a vision of where we are headed that allows us to plan for what we need in terms of specifics such as logistics, sales, and technical service,” Eastman’s Hutsell says.

Interactive digital media offer a wealth of untapped potential for virtual teams to expand their communication capacity. At the same time, the expression and direct use of the power of purpose really comes into its own with the web and intranets.

Mental models, whether expressed as outlines, lists, diagrams, or art, are easily displayed on the web. These models then become portals—quite literally as clickable links and maps—to layers of more detail about goals, tasks, results, people, resources, organization, and every other kind of information that may be important to a team’s work.

Mental models—ranging from broad perspectives on the market, estimates of risk, and organizational strategies to budgets, product designs, work processes, and agendas—have been the province of hierarchy. Typically, they are locked in the boss’s head or file drawer, developed through experience, and communicated to others as needed. This works in the world of slow pace and simple purpose where people are not expected to think for themselves. But fast-paced virtual teams facing complex problems need to share a conceptual framework of their work. And that, in essence, is a people problem.

1 Lipnack and Stamps, The Age of the Network, pp. 52-58

2 who are they?

3 Peter F. Drucker, “The Age of Social Transformation,” Atlantic Monthly (November 1994), pp. 36-41.

4 Peter Ferdinand Drucker, Management Challenges for the 21st Century, (CITY??: Harperbusiness, 1999), see http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0887309984/o/qid=948109643/sr=2-1/104-9714499-1728465.

5 Dean W. Tjosvold and Mary M. Tjosvold, Leading the Team Organization: How to Create an Enduring Competitive Advantage (New York: Macmillan, 1991); Dean W. Tjosvold, Working Together to Get Things Done: Managing for Organizational Productivity (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath, 1986).